China has become the second largest theatrical market since 2012, but when it comes to distributing foreign films in China, Hollywood has not been able to enjoy much of China’s box office success. This lack of success is due to various market-access restrictions, such as the strict quota system and the low revenue-sharing remittance rate.

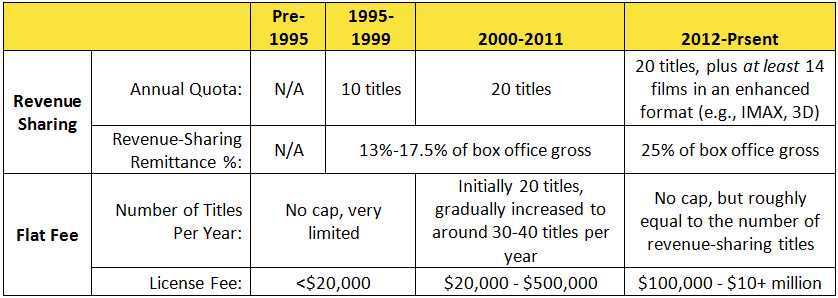

Foreign-produced films are imported into China for theatrical release on either a revenue-sharing basis or a flat-fee basis. As we can see from the chart below, China has gradually opened up its theatrical market to foreign films. The number of revenue-sharing titles went from non-existent to the current 34 titles per year. The portion of box office receipts paid to foreign studios rose from 13-17.5% to 25%. The price for flat fee titles also skyrocketed from less than $20,000 per title to over $10 million for a high-profile title.

As the 2012 U.S.-China film agreement is due for renegotiation this year, many are wondering how the quota system and the revenue-sharing remittance may change. To answer these questions, let us take a look at the significant changes and trends over the past two decades.

As the 2012 U.S.-China film agreement is due for renegotiation this year, many are wondering how the quota system and the revenue-sharing remittance may change. To answer these questions, let us take a look at the significant changes and trends over the past two decades.

1994: Introduction of Revenue-Sharing Films to Boost Depressed Chinese Film Industry

The first ever revenue-sharing film imported to China was The Fugitive starring Harrison Ford, which was released in 6 major cities in China in November 1994. The introduction of revenue-sharing arrangement is one of the key reforms undertaken by Chinese government to boost the film industry.

In the early 90s, the Chinese film industry was experiencing a downturn – box office revenues and theatrical admissions had seen a decline for several years, resulting in losses across film producers, distributors and exhibitors. At that time, flat-fee imported films were generally low-budget library titles that performed poorly at the box office, and Chinese-made films also failed to attract audiences. In this context, the Chinese government saw importation of films that had great box office appeal as a direct way to boost box office and to save film companies from bankruptcy. Additionally, a portion of the profits made from revenue-sharing titles could be carved out to fund the development of local movie industry. To serve these purposes, the revenue-sharing arrangement was designed in a way that only a small share of box office gross was remitted to the foreign film studios.

2000: Increase of Film Quota Alongside Industry Transformation

As part of the U.S.-China bilateral WTO agreement in November 1999, China agreed to increase its revenue sharing film quota from 10 to 20 and flat fee quota to 20 (growing to 30-40 subsequently). While there were concerns regarding the changing market dynamics caused by the expanded quota, the Chinese government saw this as an opportunity to transform the country’s film industry.

Revenue sharing films helped drive the upgrade of film distribution infrastructure in China. In 2001, Chinese government rolled out regulations that required theaters to meet certain criteria in order to exhibit revenue-sharing titles. For example, theaters would need to be equipped with digital ticketing systems and to be part of a larger theater chain to support cross-region theatrical distribution. Since revenue-sharing films accounted for the bulk of the Chinese box office at the time, theaters were motivated to undergo a series of changes to obtain rights to exhibit these high-grossing revenue-sharing titles.

The expanded quota – to an extent – motivated Chinese film makers to produce better films to compete with Hollywood products. With more exposure to Hollywood big-budget films, Chinese audiences had an increasing appetite for fast-paced exciting entertainment, and local Chinese industry started to produce successful blockbusters to meet such consumer demand. The, a greater variety of films were made with unique Chinese characteristics (e.g., “Chinese New Year films” ) began to emerge.

2012-present: Fast Growing Local Production Despite Film Quota Expansion

As outlined in the 2012 U.S. and China Memorandum of Understanding, China would allow at least 14 revenue-sharing films in IMAX or 3D format in addition to the 20 regular revenue-sharing titles. The box office share remitted to foreign studios is also raised to 25%.

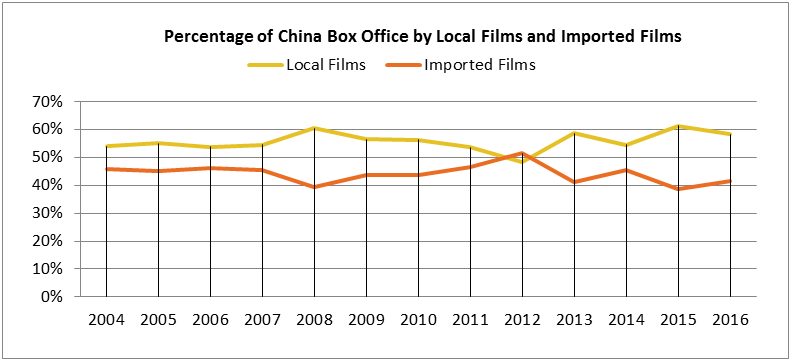

It should be noted that for 8 consecutive years from 2004 to 2011, Chinese local films collectively outperformed imported films at the China box office. When the revenue-sharing quota was first increased to 34 in 2012, the imported films reversed the trend by taking up 52% of the box office revenues, but in subsequent years, Chinese-made films consistently accounted for over half of the box office.

It appears that the expanded quotas did not hinder the development of Chinese films. Rather it forced China to further strengthen its local production through continuous exploration of different film making styles and aesthetics by Chinese studios as well as the innovative production, promotion and distribution models engaged within the industry.

Where are things heading?

Despite the tremendous growth of the Chinese film industry, the limited number of imported films allowed into China still accounted for about 40% - 45%of the box office in recent years. As such, a complete opening-up of the Chinese theatrical market in the near future seems unlikely. It will be a long time before we see China fully adopting the models currently utilized in developed markets such as France, the U.K. and Germany where there is minimal limitation on theatrical releases and the film rental remittance is around 40%.

The quota system will remain in place to protect the local Chinese industry, but, as many analysts have predicted, it may loosen up as part of the 2017 negotiation. It remains to be seen to how much the quota and box office remittance will increase. Based on what we have seen for the past two decades, the Chinese box office may be temporarily overwhelmed by the addition of imported films, but Chinese films will take the majority of the market share in the long run. History shows that a gradual increase in the number of imported films could stimulate the market, and this would likely be China’s approach in the 2017 negotiation with the ultimate goal of improving Chinese film industry’s overall competitiveness.